The FCA’s Consultation on High Cost Credit 18/12 is clear about the harm caused by Brighthouse and other rent-to-own (RTO) lenders:

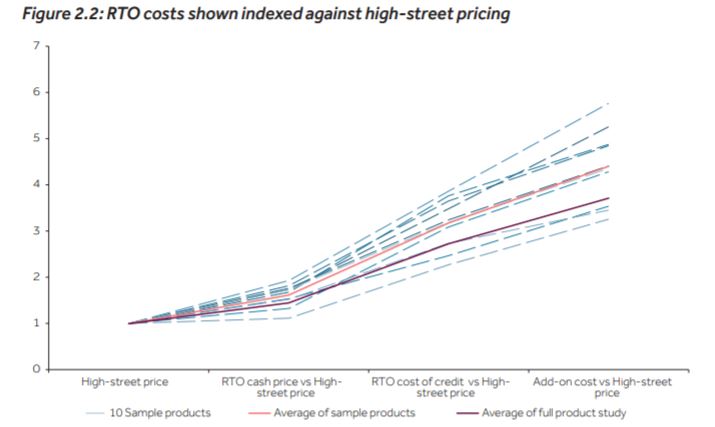

Our findings make clear that the costs of RTO are high, sometimes exceptionally so. RTO users are paying an average premium of 3 or 4 times the typical retail price of goods. At the extreme, this can be nearly 5 or 6 times …

We think it is highly likely that harm is being incurred through both the high levels of charges and the likelihood that a group of consumers would have improved economic welfare if they were denied access to RTO. For these consumers, the benefits of acquiring items through RTO are likely to be outweighed by the significant costs.

We think that some consumers would benefit from moving to other, cheaper credit sources or reconsidering their needs and foregoing purchases. Others may benefit from continuing to access RTO at a reduced price.

We anticipate that a price cap at the appropriate level may achieve the right balance between avoiding indebtedness for some and continued access to RTO at a lower cost for others.

The FCA is therefore proposing a price cap and consulting on this. The price cap could potentially be introduced by April 2019.

This article has my responses to the two of the FCA’s questions which have a deadline of 13 July. The others have a deadline of 31st August.

Q1: What alternative solutions could there be to address harm from high prices?

A price cap appears the best route.

FS17/2 described how RTO customers are a particularly vulnerable group, with declining average income and rising debt to income ratios, indicating a likely high level of consumer detriment from the high RTO total costs.

As the analysis in CP18/12 says, it seems unlikely that disclosure-based remedies would have a significant impact as RTO customers are already aware that this is an expensive form of credit but don’t feel they have an alternative.

There is also an effective monopoly, with BrightHouse having a hugely dominant market share. The RTO customer demographic is not an appealing one for commercial lenders to target, with low incomes and consequent affordability issues being very prominent. This is a market where competition-based remedies seem unlikely to be effective on their own.

Finding ways to reduce the cost of TAD and warranties would help considerably, but this needs to be in addition to an effective price cap.

Q2: What issues should we take into account in carrying out further work on a price‑cap?

The key issue is the need to reduce or eliminate the extent to which the RTO cash price is marked up considerably higher than comparable items on sale elsewhere.

Figure 2.2 in CP18/12 illustrates the extent to which the ultimate total cost varies considerably depending on how high the initial RTO cash price is set. Without an effective remedy here, placing any cap on the interest rate or other charges would be pointless as the base price could simply be marked higher.

It is often not possible to find an identical item for sale elsewhere, so RRP comparisons will often be difficult. The general market for household electrical items in the UK has long suffered from multiple models with only minor or cosmetic differences making it difficult for consumers to compare prices. For tech goods, small spec differences and software bundles (often of little importance to the purchaser) have a similar effect. But in practice, it is not hard for broadly equivalent items to be identified for most goods.

The Extortionate Credit provisions of the Consumer Credit Act 1974 provided that whether or not a colourable cash price was quoted for any goods or services included in the credit bargain was relevant to considering if a credit agreement was extortionate. One approach for RTO would to have a similar provision in CONC, saying that an unreasonable mark up contravenes the general duty for authorised firms to treat customers fairly.

This could be backed up by requiring RTO firms to report regularly to the FCA, providing a comparison of the cash price of, say, their top one hundred selling lines with average prices of equivalents elsewhere over the period.

Once a genuine cash price is set, the principle of a cap on the total cost can be applied using the genuine cash price as the base.

As PS14/16 said in relation to payday loans:

The simplicity of the total cost cap will in itself protect consumers, giving them and their advisers a simple way to identify when the cap has been breached. A 100% total cost cap is therefore the least onerous way to achieve the necessary level of protection for consumers from the harm caused by excessive charges.

Applying the same 100% total cost cap to the RTO market appears sensible. There would need to be very clear evidence to justify picking a different level.

BrightHouse in https://www.creditstrategy.co.uk/news/brighthouse-longer-timeframe-needed-for-rent-to-own-price-cap-4886 appears to be arguing that a higher cost cap is needed for longer-term loans. But if BrightHouse finds that default costs are much higher for three-year loans, this is simply reflecting the detriment caused to vulnerable customers with these loans. This harm needs to be minimised by reducing the cost of the loans and the term where possible.

The reduction in the base price and a total cost cap should enable shorter loans to be more affordable. But it is likely there will be fewer RTO transactions. However great someone’s need for a product is, if it appears improbable they will be able to meet the repayments over the life of the loan, the credit should not be given.

A simple 100% cap provides incentives for RTO lenders to give shorter terms and the extent to which this could harm the consumer is balanced by the application of affordability checks. It is not right that lenders should have an incentive to provide longer-term loans to get increased profits.

Two other issues:

- The delivery/installation charge should be regarded as being part of the cash price, and the comparison with other similar goods should be inclusive of these charges;

- Default charges should be included within the total cost cap of 100%. When collecting small sums weekly over prolonged periods, there may often be late or missed payments. Unless default charges are very low, they will be disproportionate to the payment sizes, causing stress to consumers struggling to avoid them and detriment if they respond by not paying essential bills. The doorstep lending market recognises this by not adding default charges. The RTO market either needs to follow suit or set them at a low level and manage with having them capped.

Leave a Reply